What is the Living Line Atlas?

The Living Line Atlas is a visual archive of Mi’kma’ki family placements — an attempt to put surnames back onto the land, district by district, instead of leaving them trapped under colonial race labels.

The Prototype Edition (2025) focuses on:

- Key districts like Kespukwitk, K’jipuktuk, and Chedabucto.

- Earliest appearances of core surnames in poll books, church records, and censuses.

- Patterns of reclassification from “Indian” to “Colored,” “Negro,” and “Black.”

This is not genealogy for entertainment — it is cartography for families who know they were here before the labels.

Who is this for?

People who know “Black” didn’t start the story

If your grandparents mention Native ties, if your records switch between “Indian,” “Colored,” and “Negro,” or if your family is rooted in early Nova Scotia settlements, this atlas is built with you in mind.

People tired of flat government categories

The prototype offers district-level notes and patterns you won’t usually find summarized in official reports, especially for the mixed-Native clusters that were later merged into “African Nova Scotian” lists.

Elders, advocates, and organizers

The atlas gives you language, visuals, and patterns that support community claims, land-based conversations, and reclamation projects grounded in more than just labels.

What’s inside the Prototype Edition?

Prototype Contents

- District overview pages for Kespukwitk and surrounding areas.

- Early surname clusters (Simmons, Downey, Clayton, Boyd, Cain, and more).

- Notes on reclassification patterns by district from roughly 1760–1900.

- Placement language you can reuse in your own family reports and community writing.

- Design framework for how the full 2026 Atlas will look and feel.

The prototype is intentionally compact: it’s a proof-of-concept you can actually use, not just a teaser.

2026 Full Edition (In Development)

- 8+ full district map spreads with visual overlays.

- 50+ surname movement diagrams and corridors.

- Timeline charts showing how labels changed across decades.

- Expanded district notes including Chedabucto, K’jipuktuk, Isle Madame, and Annapolis / Weymouth corridors.

- Context sections linking this work to misclassification reports and modern categories.

Email: livinglinefoundation@hotmail.com with the subject line “Living Line Atlas Updates.”

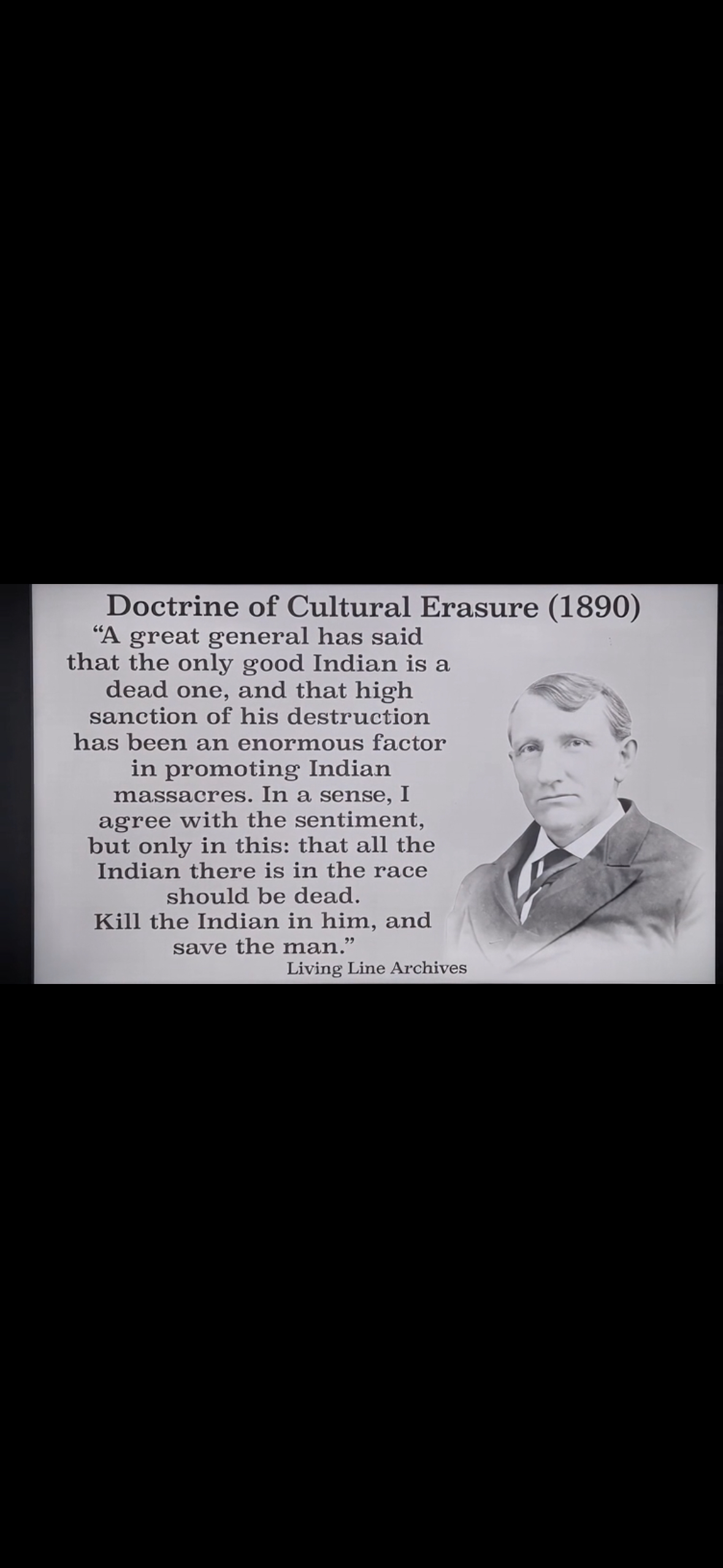

Exhibit No. 7 · Policy Mindset

Doctrine of Erasure (1890)

This exhibit presents the doctrine often summarized as “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” It explains how policy targeted Native identity on paper while keeping the person alive — the mindset that underlies the reclassification of Native-rooted families into “coloured,” “Black,” and “refugee” categories across Mi’kma’ki.

In Living Line terms, this doctrine is the backdrop for surname cases in Kespukwitk, K’jipuktuk, and Chedabucto: the paperwork changed, not the bloodlines.

Exhibit No. 8 · Policy Mindset

Doctrine of Elimination (1890s)

This exhibit presents a public call to “protect civilization” by removing Native peoples from the land entirely. It reveals the eliminationist logic that sat alongside cultural erasure — not just changing the record, but arguing that Indigenous presence itself should disappear.

Read with Exhibit No. 7, this doctrine explains why Mi’kma’ki families were both reclassified on paper and pressured off their districts through policy, dispossession, and targeted removal.

Exhibit No. 9 · Internal Doctrine

Heaven Is On Earth — Doctrine of Spiritual Subordination

This exhibit captures a moment of generational conflict: a young Native-rooted youth rejecting the colonial theology of obedience, while an older preacher defends spiritual submission to white rule. It reveals how religion was weaponized to silence identity, defuse resistance, and enforce psychological control.

“Heaven is on earth” becomes a declaration of sovereignty — a refusal to accept cosmic subordination or the internal policing that kept communities obedient.

Exhibit No. 10 · Demographic Policy

The Racial Ratio Doctrine — Demographic Engineering

A lawyer openly explains that cities and the South cannot survive unless Black numbers are reduced, redistributed, or removed — exposing demographic control as a core political doctrine.

This doctrine mirrors Canadian policy structures that sought to reduce, absorb, or reclassify Native-rooted families.

Mechanism Diagram

How Native-Rooted Families Became “Coloured,” “Black,” and “Refugee”

This diagram traces the administrative path from Native-rooted district presence to later racial labels. It shows how land-based families were converted, step by step, into “coloured,” “Black,” and “refugee” categories in the archive.

1. Native-Rooted Presence

Families anchored in specific districts — Kespukwitk, K’jipuktuk, Chedabucto — recorded in local ledgers, road lists, tax rolls, and church notes as Native, mixed, or implicitly Indigenous.

Land first · district first

2. Category Pressure

Colonial offices adopt fixed racial categories for census, taxation, and labor. Administrators are pushed to fit mixed Native communities into a limited set of boxes: “Indian,” “coloured,” “Black,” “refugee.”

Policy needs numbers, not nuance

3. Label Swaps & Splits

Early “Indian” or “Native” notes are replaced with “coloured” and “Black.” Households are split: elders noted as “Indian,” younger generations marked as “coloured” in the same district.

The bloodline stays · the label drifts

4. Geographic Reassignment

Districts and “communities” are renamed and reorganized. Longstanding Native-mixed zones are folded into new racial units: “Black community,” “refugee settlement,” or generic rural designations.

Rename the district · rename the people

5. Archival Thinning

Detailed local ledgers and margin notes disappear. Surviving records are summary tables and standardized census schedules that keep racial labels but drop early Native indicators.

Keep the totals · lose the context

6. Modern Misrecognition

Descendants searching the archive see only “Black,” “coloured,” or “refugee” categories. District continuity and earlier Native-linked descriptors are hidden behind generations of category substitution.

The families remain · the record lies

The Living Line reads this chain in reverse: from modern racial labels back to district anchors, surname continuity, and Native-rooted land presence.

Access & Pricing

Prototype Edition · 2025

The prototype is free because this stage is about clarity, feedback, and alignment with families who already know something is off in the records.

Download Prototype (PDF)Replace the button link with your actual file URL once it’s uploaded.

Full Atlas Edition · 2026

The full Living Line Atlas will be a paid archival release. Exact pricing will be confirmed closer to launch, but it is being designed as a serious reference — not a souvenir.

- Designed for families, researchers, and community advocates.

- Digital first, with the option for print runs if there is enough demand.

- Built to sit beside official reports and quietly correct them.