Exhibit No. 7 · Policy Mindset

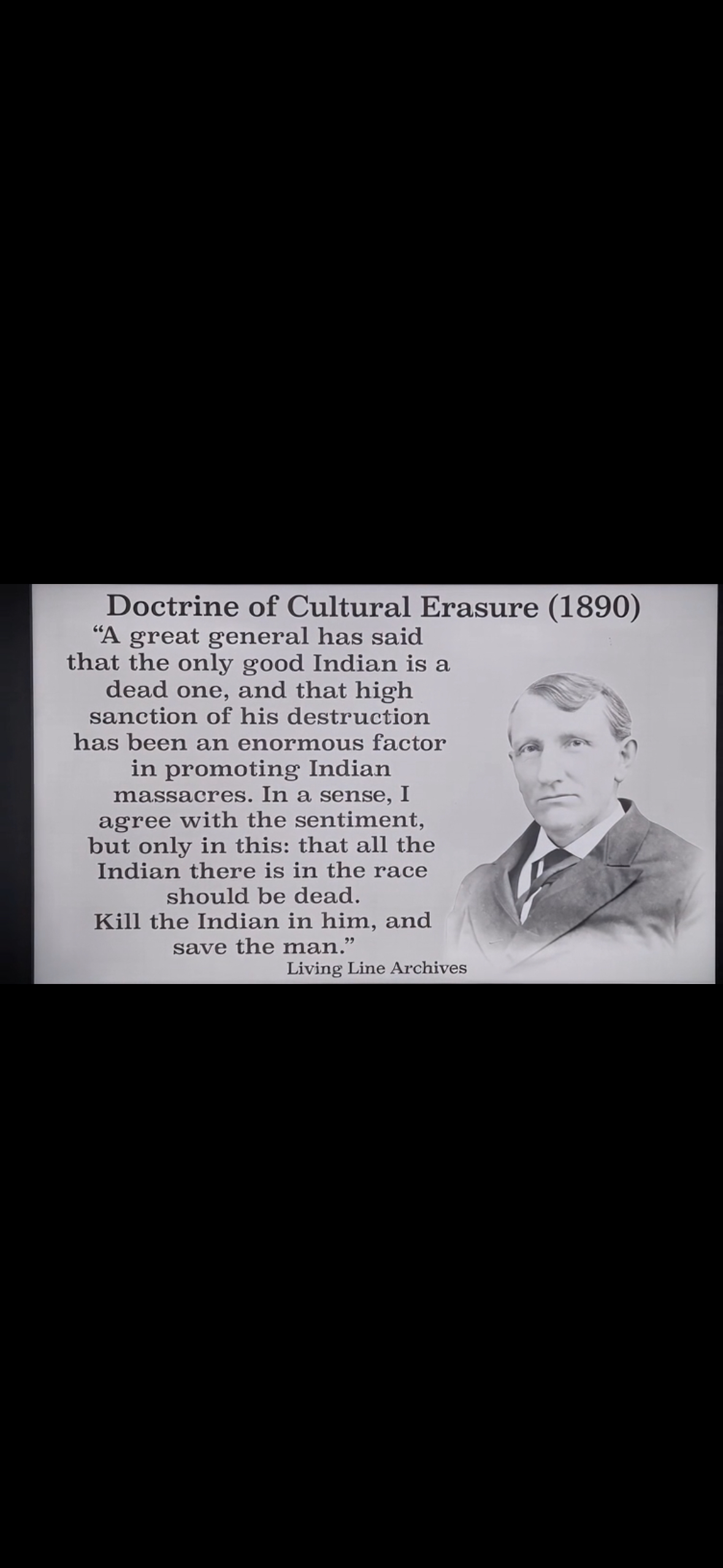

Doctrine of Erasure (1890)

How a single statement captured the policy to erase Native identity on paper while keeping the person alive — the logic behind reclassification.

Exhibit Interpretation — Living Line Reading

What this quote actually means in practice.

This quote is not just prejudice — it is policy. It captures a governing idea: erase the Native identity, and the person becomes manageable.

The goal was not only to destroy bodies but to destroy context: language, district identity, kinship, and land ties. Residential schools, forced English names, district renaming, and racial category assignment all flowed from this doctrine.

For Mi’kma’ki, this mindset helps explain why families with long-standing land presence were later recorded under entirely different labels: “coloured,” “Black,” “settled negro,” “refugee.” The people remained. The descriptions were changed.

In Living Line terms: the paperwork shifted, not the bloodline.

Connection to Mi’kma’ki Reclassification

How this doctrine appears in Atlantic records.

The doctrine of “saving the man” by killing the “Indian” in him translated directly into the record-keeping practices that affected families in Kespukwitk, K’jipuktuk, and Chedabucto.

- Early Phase — Native Descriptors: township books, road lists, and local ledgers carried margin notes such as “Indian,” “Native,” or “mixed” beside known family lines.

- Middle Phase — Category Substitution: as administrative systems matured, the same families were gradually recoded into racial categories like “coloured,” “Black,” and “refugee,” while Native descriptors fell away from summaries.

- Late Phase — Census Standardization: by the time national censuses standardized race fields, the older Native-linked notes had been erased, overwritten, or excluded from indexes. Families already on the land were now counted as something else.

The result is a documentary trail where Native-rooted families — including surnames such as Simmons, Cain, Smith, Willis, Beals, Downey, Clayton, Roberts — appear in the archive as if they were simply “Black” or refugee-descended populations, with no indication of their deeper district-based origins.

The Living Line reads these records backwards: from the imposed label back to the district, surname continuity, and land memory.

Mechanism of Erasure

From doctrine to ledger entries.

In practice, the doctrine of erasure operated through routine clerical and administrative decisions more than through open violence. The logic was simple:

- Identify: mark Native or mixed households in early local records.

- Rename: replace Native descriptors with racial terms that fit the new category system (“coloured,” “Black,” “refugee”).

- Reassign: fold these renamed families into newly rebranded districts or “communities” and treat them as homogeneous groups.

- Forget: retain only the simplified version — the later census, the racial map, the refugee narrative — and let the earlier Native indicators drop from memory.

Once this cycle completed, descendants looking backward would see only the new labels. The original Native identity had been “killed” on paper, even while the bloodlines remained exactly where they had always been.

The Living Line Position

Reversing the directive of erasure.

The families documented in the Living Line Archives were not recent arrivals from distant homelands. They were Native-rooted families already living inside Mi’kma’ki before the refugee influx, before British racial schemes, and before the census categories of the 1800s.

This exhibit is read as evidence that:

- Identity erasure was a deliberate project, not an accidental side effect.

- Reclassification into “coloured,” “Black,” and “refugee” categories was part of that project.

- District-based continuity — who remained on the land across generations — is a more accurate guide to origin than later racial labels.

The Living Line restores these families to their correct historical position: people of the land whose identities were administratively overwritten, not erased by ancestry.

If the doctrine said: “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man,” the Living Line answers: “Restore the Native in the record, and save the truth of the family.”